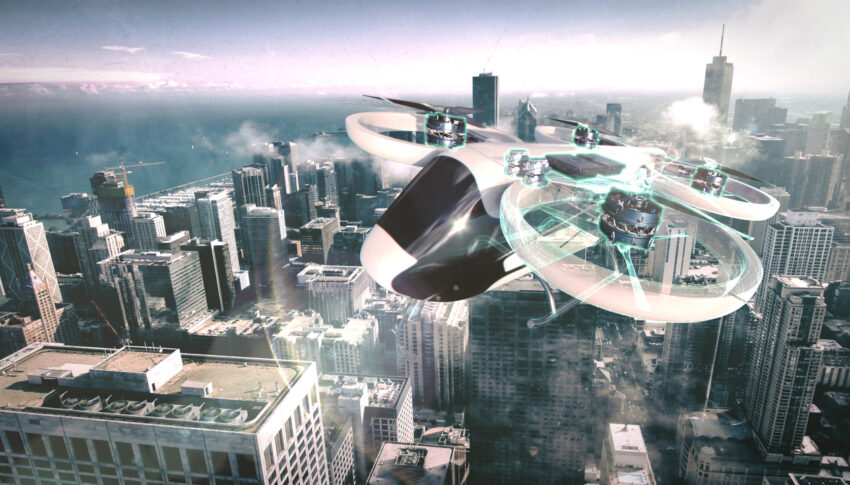

The future of aviation is incredibly exciting, with entirely new segments arising: air taxis, uncrewed aircraft, urban and advanced air mobility, electric vertical takeoff and landing aircraft, and much more.

Never has there been such diversity of proposition about what a kind of aviation will look like, with aircraft from Joby to Lilium to Archer showing great diversity of form, and even the two generations of the CityAirbus modelslooking very different to each other.

But how will these new aircraft — indeed, these new types of aircraft — be certified? The US Federal Aviation Administration and the European Union Aviation Safety Agency are taking diverging routes towards certification.

Where the FAA’s approach is essentially to evaluate a proposed aircraft’s concept of operations (ConOps) against existing certification standards, while also highlighting specific requirements for use cases that it expects to be common (like package delivery by drone) EASA is working somewhat more holistically, with a series of consultations around its pathway to certification.

We sat down with Volker Arnsmeier, EASA’s section manager for eVTOL & Light UAS, to learn more.

EASA recently closed commentary on the latest round of its Special Condition for VTOL and Means of Complianceconsultation, which took place over the northern summer 2021. The regulator is covering a wide variety of elements around certifications for VTOL aircraft: flight, structures, design and construction, lift and thrust system installation, systems and equipment, and flight crew interfaces and information.

In developing this Special Condition, and the related sets of Means of Compliance, Arnsmeier explains, “these technical specifications, together with further industry standards developed in coordination with us, serve as the technical baseline for ensuring the safety of designs. The substantiation and evaluation follows existing procedures for design approvals as known from airplane and helicopter developments.”

EASA is using this approach to what is essentially an industry segment that is disrupted from the very start. Previously, innovation and requirements for certification revolved around improvements to safety and navigation, new materials, weight reduction, and so on, within the bounds of an aircraft that largely looked like previous generations.

By contrast, says Arnsmeier, “the situation of eVTOL was very particular. Around the same time, various industries approached us on the possibility to approve rather different architectures of designs, but with fairly common new features — namely electrical propulsion, multiple lift/thrust units, fly-by-wire flight controls and a vertical take-off and landing capability — and with the same operations in mind in terms of innovative air mobility. Our analysis of existing airworthiness specifications and operational rules indicated that significant modifications would be needed to create a common basis, in particular with respect to airplane and helicopter rules, in an urban environment.”

And that’s just for the passenger aviation side of things: as drones, uncrewed aircraft and cargo systems grew in visibility and capability, they also needed to be considered within that environment of licensing, air traffic management, operation, maintenance, and so on.

Parallels with existing products and segments are helpful — to an extent

“As regards urban air mobility, there are some clear connections to the existing operational and technical requirements for commercial air transport by helicopters flying in such congested areas,” Arnsmeier explains. “Already there, the current airworthiness requirements provide for safety objectives similar to a commuter airplane or large rotorcraft, even for few occupants such as in a helicopter emergency medical helicopter. And these more stringent safety objectives are then referred to by the operational requirements.”

Within other concepts of operations — a small package delivery drone, for example — proportionately different safety objectives are considered. Wherever possible, safety objectives are technology-agnostic, enabling the maximum amount of operational read-across.

The FAA, for its part, outlines its requirements in the 57-page 2017 Order 8130.34D [PDF], which “establishes procedures for issuing special airworthiness certificates in the experimental category to unmanned aircraft systems (UAS), optionally piloted aircraft (OPA), and aircraft intended to be flown as either a UAS or an OPA under the designation ‘OPA/UAS’”.

The FAA also publishes proposed airworthiness criteria that are used to issue type certificates for specific uncrewed aircraft, with ten (including the Amazon Prime Air MK27) released in November 2020.

A key part of the process to establish the basis of certification is either the FAA-certified G-1 issue paper or the EASA equivalent, the Certification Review Item A01. For example, US-based Archer says it has achieved a G-1 milestone, while Germany’s Lilium has a CRI-A01.

While certification bodies are bound by specific legal and rulemaking procedural requirements, EASA is also taking advantage of online publishing and commentary, as well as update, versioning and notification options, the agency’s Arnsmeier explains. “Modern tools allow us to transform the content eventually into so called eRules. Those can combine rules, guidance and advisory material in a context and thus enhance readability.”

At the same time, companies developing new aircraft are also creating new digital systems to manage the compliance demonstration and finding process in order to make the process more efficient.

“Compared to the old days,” Arnsmeier says, “data and information exchange is purely electronical with filing systems that enable a secure transfer and storage. Commenting, rejection and acceptance are ideally accomplished through these tools and are traceable, allowing also the applicant to better understand the status of the authorities review.”

As more and more aircraft in the UAS, UAM, eVTOL and other categories seek certification, regulators — particularly the FAA — will be keen to demonstrate their independence and dedication to the best principles of aviation safety.

In many ways, any kind of certification is always and inherently an iterative process, no matter the size of aircraft, as EASA’s Arnsmeier highlights. “Looking at the airworthiness specifications for, for example, large aeroplanes, the CS-25has been first issued in 2003, based on the previous JAR-25. Now we are at amendment 26. We expect that also the content of SC VTOL could need revisions. The initial certification programs will show whether it is necessary to introduce changes or not. Then we would continue to convert it into a Certification Specification.”

Across the industry, it will be fascinating to see how the certification of these new aircraft and new market segments evolves.

Author: John Walton

Published:10th February 2022

Feature Image: Copyright Rolls-Royce