As the aviation industry continues its research at pace into hydrogen power for commercial aircraft, it’s not just the airliners’ main powerplants that need to be designed to use H2 — it’s the entire aircraft, including the auxiliary power unit, or APU. With a new programme, HyPower, running from its technology demonstrator hub UpNext, Airbus is exploring how the technologies and pathways for hydrogen fuelled APUs aboard a testbed aircraft, and we sat down with Giulio Zamboni, Airbus’ head of demonstrator, to learn more.

“HyPower is about exploring the balance between the auxiliary power that is generated by the engine and the one that is generated by the auxiliary power unit, typically installed in the rear part of the fuselage,” Zamboni tells us. “Our ambition is to understand what it takes to bring the technology to flight, understand the implications in terms of system integration, and we’re very interesting to understand what it takes to bring these experiments to fly in terms of permits to fly and also the implication for potential certification in the future.”

Commercial aircraft use the same type of fuel for the APU as for their engines, so there’s an inherent need to run research and development to determine the size of the APU, its location on the aircraft, how to fuel it, and — most crucially — whether it should be a fuel cell or hydrogen combustion engine.

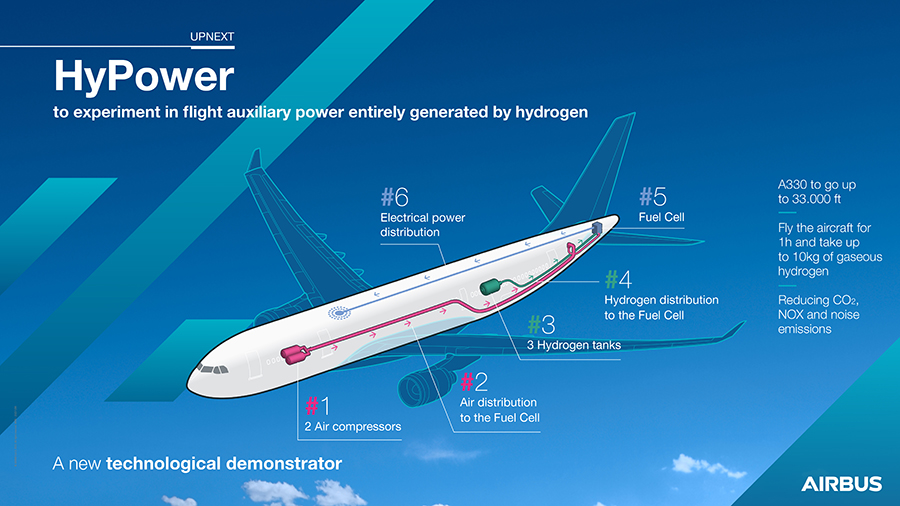

HyPower, Zamboni says, “is all about trying out whether the electricity power that we use for auxiliary power can be generated by the usage of hydrogen in a fuel cell installed on an aircraft.”

The programme will install the fuel cell in the APU’s traditional space at the rear of a testbed Airbus A330-200 that will use kerosene power for its main engines for test flights of roughly an hour. Airbus is in the process of deciding whether to use one of its existing flight test aircraft for HyPower or to source an A330-200 from elsewhere. In the context of the open question about the size of airliner that Airbus will select for its first hydrogen production aircraft, currently planned for the mid-2030s, it’s notable that the testbed is a small-medium widebody in the much-discussed middle-of-the-market category.

There are three elements to the HyPower system: air compression and distribution from the aircraft’s main compressors to the fuel cell, hydrogen storage from new 10kg tanks in the rear baggage hold to the fuel cell, and distribution of the energy from the fuel cell for the aircraft’s electrical use. Little of the architecture is yet fixed at this point in the programme.

Asked whether the hydrogen will be gaseous (and thus at relatively normal operating temperatures) or liquid (and thus supercooled), Zamboni notes that “we don’t see major differences, in terms of distribution of hydrogen. The difference here, that you mentioned is much more about the usage of it to generate the energy that is required. We are advancing some of the technologies, we are maturing some of them, and we are looking at a number of options.”

HyPower will use as much commercial off-the-shelf technology as possible in order to explore new supply chain options, suppliers and technologies.

In terms of timelines, Zamboni concludes, “this year is much more about investigating and finding the right architecture for the integration of the systems. Next year is much more into testing the novel systems on the ground, so that we can build the confidence to then bring it to flight. Next year as well, it will be… the modification of the platform to bring the novel systems on flight, and then 2025 is all about the flying.”

Published 29 June 2023