The growing use of robotics and the development of cobotics — collaborative robotics — within aviation is being accelerated alongside everything else as the industry looks to emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic. From small swarming camera robots to intelligent, AI-driven inspection machines, all the way through to technicians either in exoskeletons or remotely fixing grounded aircraft from halfway across the world, the prospects are almost endless.

“Robotic technologies can make a real difference in how a task is managed, learnt or completed,” Nick Sharples, head of technology delivery – training and support at BAE Systems, tells us. “Within a manufacturing and in-service environment the current applications for robotics are typically focused around assistance with repetitive procedures to increase throughput, the task repeatability and increased quality assurance.”

Commercial aviation has traditionally involved a lot of technicians doing a lot of manual work, often difficult and in hard to access spaces. But when it comes to production and maintenance, repair and overhaul, says Rolls-Royce in-situ technology specialist James Kell, “we’re interested in all sorts of things to help us inspect better, get into different nooks and crannies and find out different areas of investigation to perform inspection and ultimately decide whether something’s safe to fly on — or not — visually. We’re investigating a range of different kinds of automated aspects of doing that.”

Enter the Intelligent Borescope, which has reduced the data processing time for engine inspections from 90 minutes down to ten.

It uses a 3D colour image-generating scanner on its tip to capture images from inside an engine, all the way up to the size of high-pressure turbine blades. The images are analysed by an artificial intelligence app in the borescope handset before being uploaded to the company’s proprietary cloud.

A turning tool automatically rotates the engine stage, positioning the blades, and then tells the borescope to capture another image. Back in the app, these images are processed using technology akin to facial recognition, mapping the blades for inconsistencies or irregularities. An operator then reviews and approves the process.

Rolls has also been working on industrialising its COBRA snake-type robot platform, as well as the FLARE heads that together are able to repair coatings inside an engine’s combustion chamber — on wing.

But that’s not the only collaboration that’s been going on in the industry.

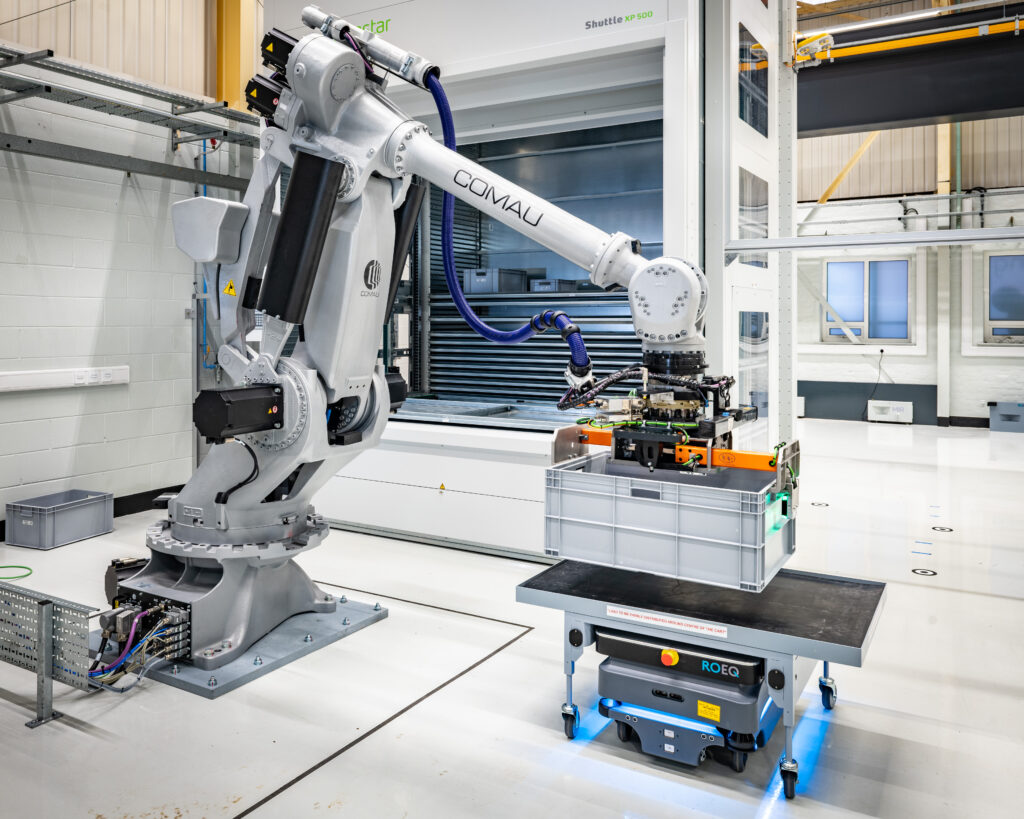

Cobots — collaborative robots — work alongside humans

“Within our Factory of the Future at Warton, Lancashire, we are further developing the use of cobots, which can sense the presence of humans, thanks to intelligent sensors,” Sharples explains. “They will know if a worker needed a break, or has picked up the wrong tool. They will recognise operators and automatically load optimised individual profiles using wireless technology, delivering tailored cues and instructions.”

“The human-machine interface is key. While human hands will always be able to do some jobs better, cobots can potentially provide greater repeatability, accuracy and strength,” Sharples notes.

BAE has also developed what it calls the Intelligent Workstation on its Typhoon production line, in conjunction with the UK’s University of Sheffield’s Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre and Fairfield Control Systems. It’s fitted with new technologies including operator recognition and a sensor-enabled cobotic arm, as well as integrated sensors to ensure safety for the people working directly with the robots.

“The technology allows the worker to make strategic decisions while delegating to the cobotic arm repetitive, machine-driven tasks which require consistency. This allows engineers to focus on highly-skilled tasks, adding greater value to the manufacturing process,” Sharples explains. “The workstation is programmed to recognise operators and automatically load optimised individual profiles using wireless technology. It automatically delivers tailored cues and instructions, suitable for their level of expertise to guide them through practical tasks. This allows employees to work at a greater pace, with increased accuracy.”

Almost inherently, developments in technology and connectivity will allow any and every operational parameter to be recorded, analysed, and processed from robots and cobots.

“This will help us quickly inform the digital twin of the product and the overall operation, allowing analysis and optimisation with the testing fully carried out in a synthetic environment before downloading and deploying any updates back into the factory or MRO facility,” suggests BAE’s Sharples. “It’s about moving from a facility being a building full of machines to an environment where every machine and the sensors within them feeds data back in. It could be as simple as a sensor on a component making sure it’s not exposed to high heat, or as complex as a robot system, feeding back all kinds of information: about its position, the tools it has, the job it is doing”

Also to come is an interesting future of teleoperations, as robot dexterity and haptic feedback technology converge. With very low latency connectivity as a prerequisite — but one that is by no means rare — being able to remotely operate a robot from thousands of miles away is already a reality in industries like mining, so well within aviation’s horizon.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=63iUx7kf7dY

Looking to the future, both Rolls and BAE are involved with the UK’s Robotics Growth Partnership, which brings a variety of players from across industry, academia and the public sector together.

The goal there, Kell says, is “trying to describe different problems that exist in different industries, and how we might be able to better collaborate together. What happens is, we all end up making our own thing to fix our problems. That’s something we’d like to try to not have to do in the future.”

The industry rollcall within the group includes “National Rail, Siemens, Jacobs, the National Nuclear Laboratory, Severn Trent Water, the Army — people, you might not really necessarily think of,” Kell explains.

Part of the goal is essentially turning robotics into a commercial off-the-shelf — or at least an industrial turnkey — approach. Need a robot about X size to do task Y? Try the model B3.

Beyond that, suggests BAE’s Sharples, “in the future you could see that humans might move up and down a production line propelled by exoskeletons. A mechanical frame will extend to help someone reach a heavy part and hold it steady. With a turn or nod of an eye, a worker could control his or her movements.”

With the speed at which technology continues to develop and be deployed — Rolls-Royce was only first starting to demonstrate its COBRA and FLARE robots at the last Farnborough Airshow in 2018, and now it is industrialising the technology — that future could well be closer than we might think.

Author: John Walton

Published: 16th November 2021