Stark pictures of commercial aircraft being recycled have been a hallmark of the COVID-19 era — and, in its most recent in-house recycling of an Airbus A319, Finnair managed to recycle all but 290kg of a 40,000kg airframe.

The global demand trend is firmly towards greater sustainability, Elina Kopola, founder and director of design house TrendWorks and herself a specialist in the colour, material and finish (CMF) of aircraft cabins, tells us. Kopola also recently founded the Green Cabin Alliance, a new initiative joining up designers, suppliers, manufacturers and recyclers to make the processes and products inside the aircraft cabin more sustainable.

Recent sustainability drivers, Kopola says, include “the IPCC report in 2018, the possibility of limiting global warming to 1.5°C, and the direct action of groups like Extinction Rebellion.” All this, she says, “has resulted in real change in people’s values, consumer behaviour, and purchasing shifts towards a greener economy.”

But what about the cabin interiors, with all their carefully engineered plastics? “Aircraft cabins are not currently recycled,” Tony Seville, managing director of AIRA, the Aircraft Interior Recycling Association (also a member of the Green Cabin Alliance), tells us. “Sold yes, landfilled yes, upcycled into furniture sometimes, but actually broken down, processed, segregated, separated, and recycled like a car is recycled, no.”

“I expect, between now and 2030,” says AIRA’s Seville, “the manufacturing part of the aircraft interior industry to step up to the plate and recycle with AIRA as we push on with our recycling and research, with the likes of [plastics manufacturer] Sekisui Kydex.”

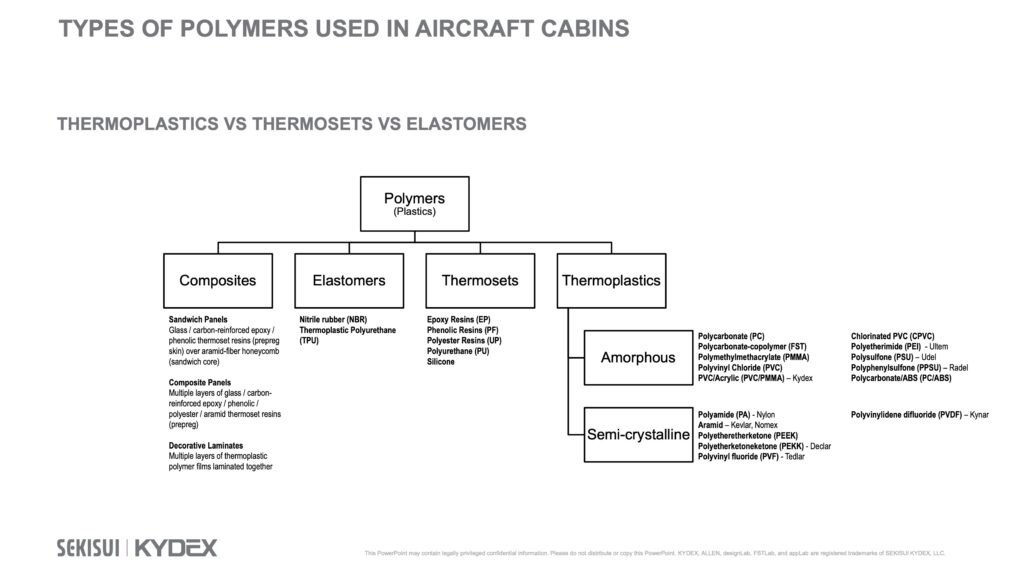

Part of the complexity is the number and kinds of plastics inside the cabin

“Plastics, more generally known as polymers, are used in many different areas inside the pressurised cabin of commercial transport category aircraft,” Michael Miler, senior business analyst at Sekisui Kydex, also a member of the Green Cabin Alliance, tells us. “Different polymers are used for different applications, and some of them serve very specialised purposes, such as reducing carbon emissions by reducing weight or keeping passengers safe by meeting the most stringent FAA flammability requirements.”

Critically, Miler notes, “polymers differ significantly in their ability to be recycled based on their basic chemistry.”

Moreover, in the aviation context, plastic materials of all kinds can have glues, fillers, flame retardancy and other coatings, and are often sandwiched together with other materials, making post-use processing complicated or even impossible.

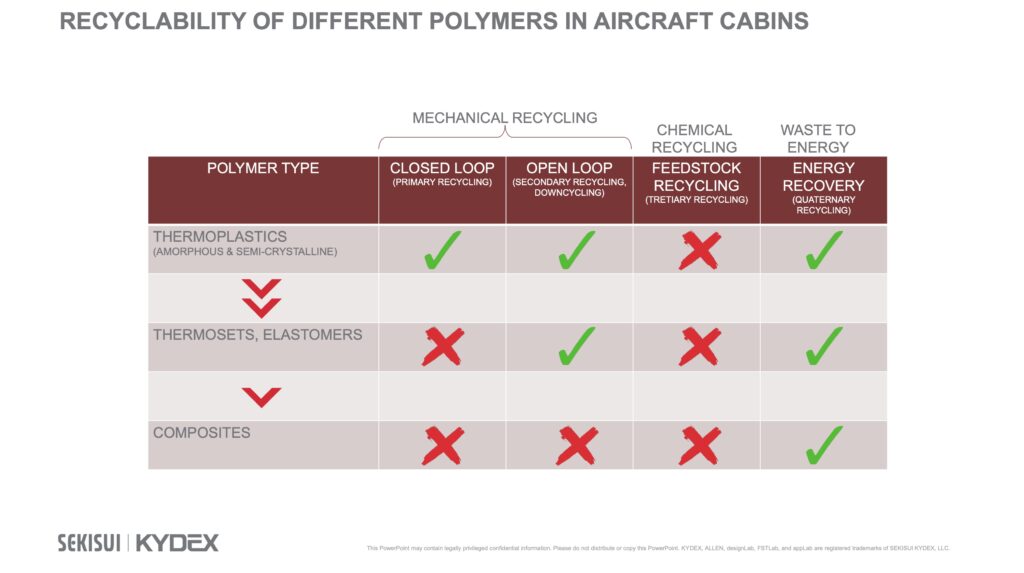

Rigid polymers are eligible for recycling, upcycling or downcycling — the open loop where a material sees a change of use, for example from being part of a cabin to being turned into the trays in an e-commerce warehouse, or as a utility pipe.

“Thermoplastics are the most recyclable polymers and can be re-melted into new items after undergoing mechanical recycling,” Miler says. “While thermal reprocessing and flame retardants can have unwanted negative effects to the recyclability, many of these problems have technical solutions.”

Owing to their chemical structure, thermosets, on the other hand, cannot be re-melted, while elastomers are markedly more difficult to recycle than other plastics. There are options for recycling these materials, but they are less commercially viable than thermoplastics. This makes the open-loop recycling change of use model much more appropriate.

Composites also add complications, explains Miler. “Composites, such as laminates or sandwich panels, represent an additional challenge to recycling, in that the multiple constituents of a composite material — which can be thermoplastic, thermoset or even a non-polymer, such as glass or carbon fiber — must be separated first before each individual component can be recycled.”

By and large, though, and across the various kinds of plastics, Miler concludes that “mechanical recycling of thermoplastics remains the most viable target for true closed-loop recyclability, both from a commercial and technical standpoint.”

Commercial aircraft cabins contain thousands of kilos of plastics

So how much plastic, and what kinds, are in the cabin of your average commercial jet?

“There is no data as such that we know of, but we carried out some research on end of life aircraft,” Tony Seville of the Aircraft Interior Recycling Association says. “On an Airbus A320 or Boeing 737, there is about 600 to 700kg that we can actually see in the cabin: seats, parts, windows, window surrounds, scratch panels & PSUs etc.

“Then there is all the plastic we can’t see, or don’t notice — which amount to a lot more, which I would say would be around 2500kg in total,” Seville says, explaining that this would include “all textiles — seat covers, carpets & curtains, which contain plastics — and plastics from the monuments like lavatories, galleys, overhead bins, et cetera, but it’s difficult to know the true figure.”

Kydex’s estimate suggests that somewhere between 3000–6000kg are typically used within the cabin of commercial jets, which would sync at the lower end. The company estimates that thermoset composites form upwards of 55–75% of the interiors.

“Thermoplastics are predominant in seat trim, passenger service units, electrical insulation, windows and window shade assemblies, non-textile floor covering and various small parts. Depending on which estimates are used, thermoplastics account anywhere from 10 to 45% of polymers used,” the company’s Michael Miler explains. “It is therefore probably reasonable to assume a 75–25 split between thermosets and thermoplastics used within the pressurized cabin of commercial transport category aircraft.”

Fundamentally, it’s clear that aviation needs to gather data, analyse it and make informed choices on which plastics have lower emissions, higher recyclability and thus a lower overall carbon footprint, to allow substitution of more responsible materials in the place of those that have a larger footprint.

Today’s primary challenge is around identifying the kind of plastic in a particular item

Since plastics are, by and large, recycled differently and can’t be intermingled, strict separation is needed to ensure that a thermoset piece doesn’t end up in the same bin as a thermoplastic or elastomer, for example.

Additives — Kydex cites stabilisers, lubricants, process aids, dyes, flame retardants, smoke suppressants, impact modifiers, and more — can also affect how, or even whether, a piece can be recycled.

“Solutions to correctly identify all polymer waste could include standardised and unambiguous markings during secondary plastics processing,” including injection molding or thermoforming, Miler says, “and complete material traceability from the source to the end user. Markings could be physical part markings as well as other more advanced markings.”

These might include something like a barcode, QR code or RFID technology, but the fact that many of these plastics are cut, trimmed and formed (and then sometimes cut and trimmed again) adds complications.

“In the apparel industry QR code and NFC (Near Field Communication) in garment labels are currently the most common consumer facing solution,” TrendWorks’ Elina Kopola notes, explaining that this kind of solution “contains product care info but also info for recycling and disposal. The downside is that these label can easily become detached from the item.”

Kopola cites Adidas’ “Infinite Play” recycling scheme as best practice from another industry often cited alongside aviation in the sustainability stakes.

Some kind of sticker on final products could be an option, as could using techniques like Kydex’s Infused Imaging for the identification, or even some sort of stencilled code along the lines of security markings used for corporate IT devices.

But across industries, Kopola says, companies “have now come to the realisation that to retain market share and build a loyal customer base they need to limit their environmental footprint and transparent in their actions of how to achieve it.” To that end, she recommends: “take the consumer on the journey, communicate and be transparent [around] goals, actions, and results. It’s the passenger that will shape our future industry.”

Published: 5th October 2021

Image credits: Sekisui Kydex