Our ‘Value in Action’ series shares case studies that demonstrate the real value of our partners’ digital solutions in aviation. Here we find out why Project4 Learning Lab was selected for a large-scale Agile Transformation project for a big multinational, the process and outcome, and the lessons learned along the way.

In Part I, we described our journey in Leading an Agile Transformation for a complex hardware product development program for a large multinational company in a highly regulated industry.

We didn’t consciously set out to implement ‘Agile’ or lead an Agile Transformation. Indeed, we didn’t even have either a template or a master plan describing how we were might deploy Agile. However, we did believe that there had to be a better way of developing programs in order to be able to meet the challenging project brief we were given.

The one thing we did have was a very motivated core team that was willing and eager to try something new, and our client organisation was willing to let us experiment.

So, we just threw ourselves into the task.

We found a space for the initial team where we could all sit together, we bought a coffee machine, and we got hold of some whiteboards and flip charts. We also started to tentatively plot our course and most importantly – we set out with a mindset to be open and willing to learn.

We recognised early on that that mindset, and the behaviours it would provoke, would play a key role in our ability to deliver the project to everyone’s satisfaction – but we also knew that we might very well have to change some of the operational structural, processes, and protocols that could hold us back.

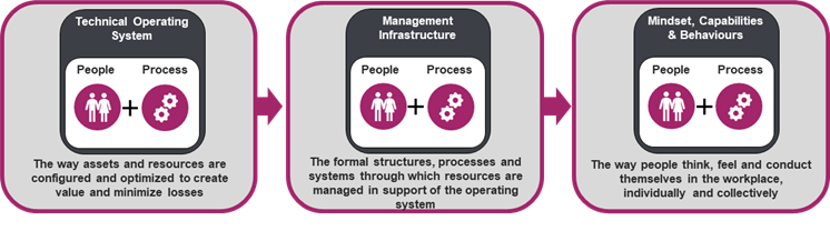

Our learning in this Blog is therefore grouped around 3 highly connected dimensions:

- Technical Operating System

- Management Infrastructure and Mindset

- Capabilities and Behaviours

We knew from the outset that finding the right balance between those three dimensions would be an important part of our journey.

1. Technical Operating System

The way assets and resources are configured and optimized to create value and minimize losses.

Standard Diary

Introducing a Standard Diary was an important trigger for us, a device through which we could break old habits and embed new ones. This wasn’t about putting additional meetings on top of existing ones – we genuinely aspired to deliver a Minimum Viable Bureaucracy.

To help deliver this goal we reviewed the ‘day in the life’ analysis of our team leaders, and were rather shocked to discover how little of their time was spent on value adding activities.

It transpired that up until that point they had spent the majority of their days bouncing between meetings with different stakeholders, or firefighting the latest crisis. We needed to somehow provide them with the necessary time and space to plan and lead effectively. This meant we needed to challenge some of the existing processes such as the 2-day program reviews, and the weekly 3-hour Product Technical Meetings. We asked ourselves the question: How much value did these meetings actually create?

We moved to a Standard Diary across the project to include sprint launch, planning, and retrospectives – as well as a cadence of daily stand-ups across the team. Every part of the process was interrogated to understand its net value. This felt a little contentious at times, but freeing up valuable capacity was an absolute necessity if we were to meet our deadlines.

Sprint Planning and Delivery

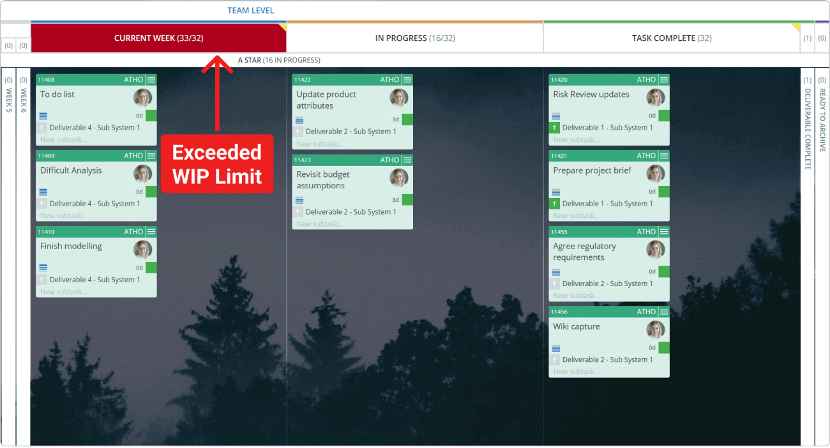

We decided to employ 6-week long working ‘sprints’ – and used ‘planning poker’ and WIP limits in Kanban boards to highlight the bottlenecks and chokepoints that requiring action during the planning process. Once we had completed our preparations, every team’s workload was visible to all, and they were better able to manage their WIP using Kanban.

Analysing work capacities during the planning helped us to remove unnecessary work – albeit one interesting challenge we faced was the perception that we were micro-managing the process as people had never been asked about the structure of their working days in such detail before.

But we wanted teams to be able to commit to tasks with an increased level of confidence about the time they we spend on them, and therefore be able to gauge whether they had ‘had a good day’ in terms of productivity or not. It was important to emphasize that this had nothing to do with managerial oversight.

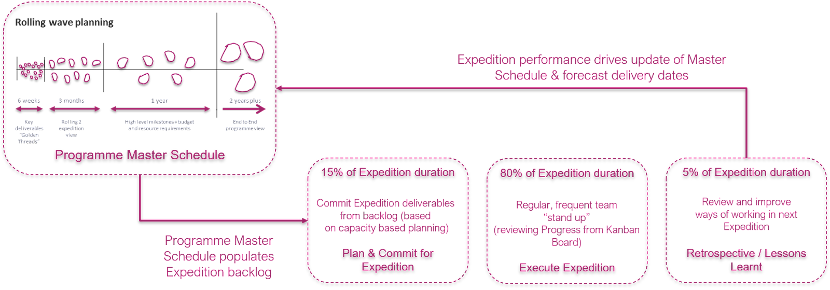

Perhaps controversially in the Agile world, our program Master Schedule and Rolling Wave Planning functionality was an important part of our system. This approach created a work plan that contained key customer deadlines, and cross-program dependencies, as well as important synchronization points in the design process.

Through the Sprint Planning process we were able to provide internal and external stakeholders with the levels of visibility and transparency they’d never experienced before – as well as being able to see the overt effects of the team’s actions on the overall product and program. The important learning here was to commit to and maintain all aspects of the Master Program such that it becomes a really useful tool for everyone in the process.

Also by choosing to have 6-week work ‘sprints’, and involving the teams in the planning and logistics process relating to the amount of time required, actually served to make those teams tighter, more efficient units. On reflection, perhaps a maximum of 4 weeks for the work sprints might have been a more productive idea (providing a better balance between planning and delivery), but without going through the process we’d have never realised that would be the case.

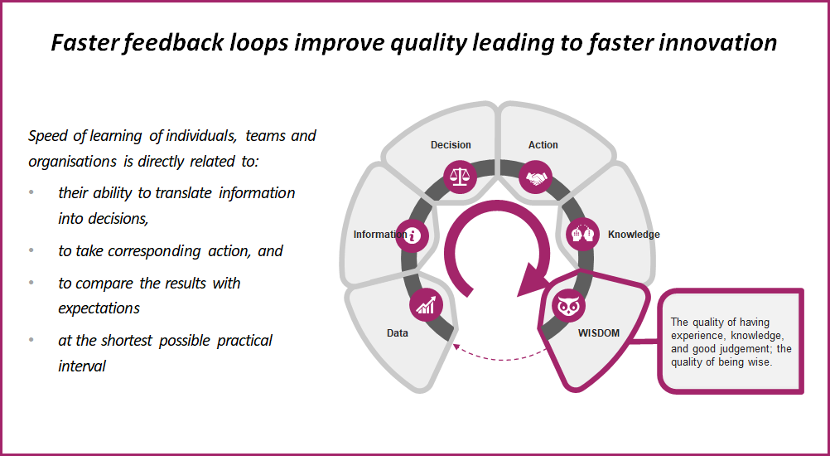

Knowing what we need to know, and when

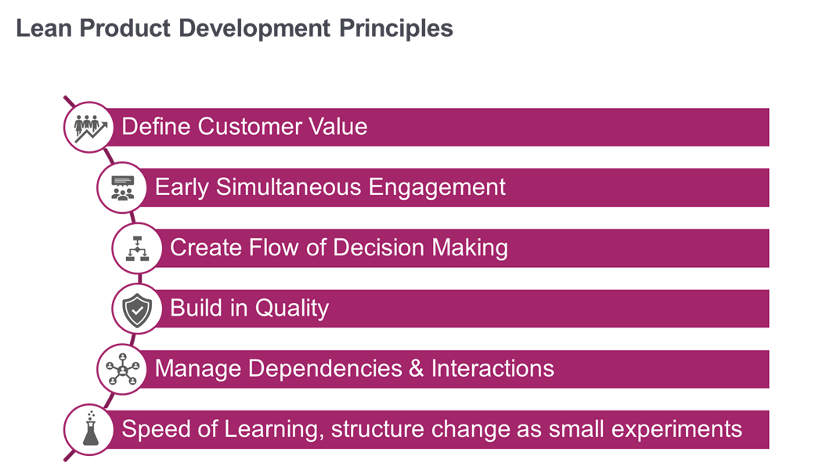

Speed of learning was crucial, so knowing what we need to know (and when we needed to know it) became something of an obsession. We identified and sequenced our key technical and program decisions points in order to improve the flow of work – and to also minimize the risk of decisions being made based on flawed assumptions.

Visualizing this with the teams improved collaboration and increased every team’s appreciation of how their work interacted with and was linked to others. This eventually became a vital information feed into prioritizing our backlog ahead of sprint planning.

Synchronization and Enabling Collaboration

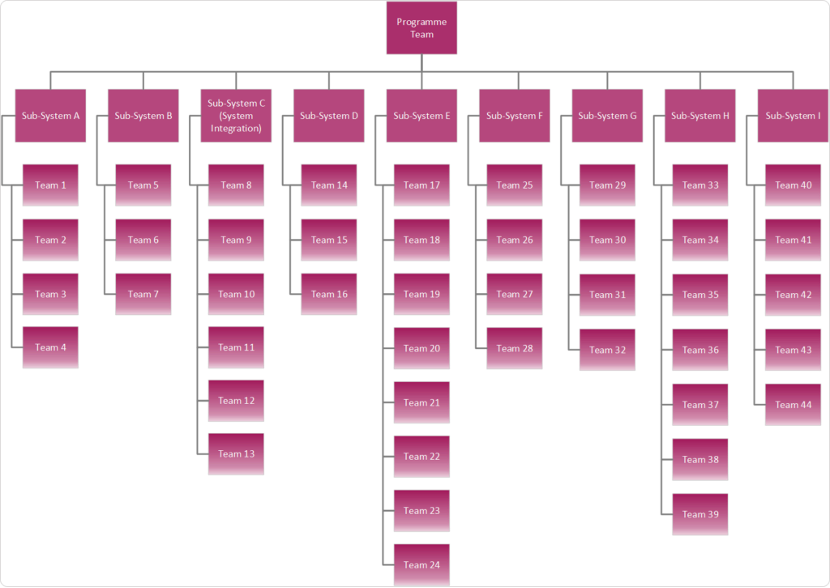

In order that we ultimately delivered a meaningful and fit-for-purpose product, it was vital that all of our teams collaborated and synchronized their work. Of course managing interfaces across teams is always a key challenge, particularly when you are working on an inherently complex project..

So planning, sprint reviews, and retrospectives became an important part of the project scaffolding, allowing various strands to remain aligned. As part of the planning activity, we introduced ‘Speed Dating’, where we allocated specific time for the teams to discuss any cross-team dependencies and encourage them to develop mutually-beneficial synchronizations, but making sure these were framed against an aligned set of priorities at the program level.

Bringing the whole project team together by using this framework built an incredible amount of empathy and trust. It also encouraged a culture of reflection and mutual learning that delivered improvements across a range of other projects.

2. Management Infrastructure

The formal structures, processes, and systems through which resources are managed in support of the operating system.

Align around a compelling vision

We had to deliver to a demanding customer with a particularly challenging set of requirements – so we started this process by trying to visualize what seemed to be a ‘crazy goal’. From the outset we convinced ourselves that we could meet the challenge, and enthusiastically flushed out as many of our self-limiting beliefs that might serve to hold us back. We had been told the organization would support us in any way it could, we just needed to ask.

We had an explorer come and give an inspirational talk about how he had used a kite to accelerate his expedition across Greenland and in doing so break a number of records. We also invested time in sharing stories where people had achieved amazing things by believing in their own ‘crazy goals’. This generated amazing energy across the team and a real determination to try and deliver something exceptional.

After some early positive steps toward achieving our collective ‘Crazy Goal’, we got to a stage where it felt like we were not quite making the progress we had hoped for. A casual conversation with one of the team members highlighted an issue that none of us had considered during the buzz of starting a new project.

Such was the enthusiasm and commitment shown by many individuals, teams were inadvertently committing to deliverables they really didn’t know how they could deliver. Everyone, it seemed, had got a little carried away. Moreover people were then concerned about asking for help, as this could be perceived as letting others down. So we needed to develop a way to help team members raise concerns in a healthy and productive environment.

Daily Stand-Ups

Initially, we started with what we dubbed a daily stand-up at Program level. During these sessions people were encouraged to explain what they were doing, what issues they were encountering, and what they think might address them. These proved to be hugely popular – and the secret to their success was that they gave people permission to ask for help.

There was plenty of experience of ‘Short Interval Control’ elsewhere in the business, but historically this approach would run for a relatively short period of time before petering out and ‘normal’ management routines restored. So it was a something of a culture shock for many to find out that there would actually be meeting every day for the entire project.

In Part 1, we described how one engineer didn’t initially see the point of such meetings – but he very soon changed his mind. When working effectively, these stand-ups would be no more that 15-30 mins in duration, and each team developed some of their own rituals around the daily stand-ups, for instance if you were late more than three times you’d be buying cake. Our teams soon became a community.

Most importantly, these stand-ups provided leaders with a platform to lead, and an informal social mechanism through which they could have candid conversations with individuals. And of course, they also presented team members with an opportunity to manage upwards.

Visual Performance Management

Over the course of the project we carefully evolved a workable approach to Visual Performance Management. We started off with something simple – paper sheets stuck to a wall of the Program Management Office. This naturally progressed to a Tiered Visual Performance Management (TVPM) system, where each team had their own performance management board, either a physical one or something hosted online.

We felt it was important to give teams the freedom to find their own way to deliver – and this proved to be one of the areas where teams experimented the most. This was largely influenced by the composition and personalities within each team, but it was also accelerated by teams exploring and employing intelligent digital options of their own creation.

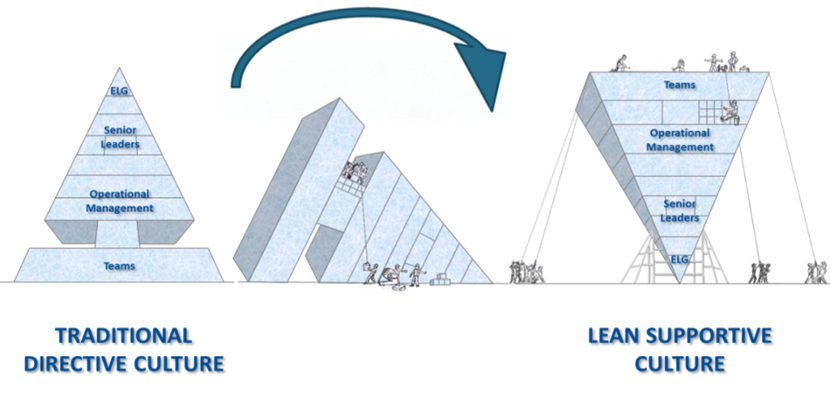

The performance management system was used as part of the standard diary cadence, and provided the infrastructure to effectively invert the conventional corporate pyramid. This happened by engaging the majority, doing our best to identify and measure the key metrics correctly, and by providing easy to navigate status updates. Our role as leaders was to better enable, embolden and empower teams, and help them deliver against strict deadlines by removing as many impediments as possible, and just being there to give them all the support they felt they needed.

3. Mindset, Capabilities and Behaviours

The way people think, feel, and conduct themselves in the workplace, individually and collectively.

Mindset is everything

The prevailing mindset across the organization at the time was that all programs overspend, over-run, and fail to deliver against the initial targets that had been set.

This backdrop, in conjunction with the risk of significant financial penalties should we not deliver, was in danger of creating an extremely negative and pessimistic environment in which to launch the new project.

We talked earlier about the importance of alignment and how we worked as a team to instil a sense of community and belief, that perhaps there could and should be a different and much better way to work.

We therefore wanted to break out of the prevailing mentality and encouraged everyone involved to try new approaches. Our objective was to shift the dialogue from a focus on failure to one that celebrated learning through discovery. Our hypothesis was that if we could challenge some of the deeply rooted beliefs and more established ways of working head on, we could potentially unlock the pent up potential and enthusiasm of the entire project team.

It would be false to say that everyone was on board from the get-go, but we had enough momentum to really start to make a difference early, with a growing number of people willing to experiment and try new ways of working. We quickly started to see the benefits, and the energy remained high as we overcame a series of negative perceptions and celebrated a series of tangible wins together.

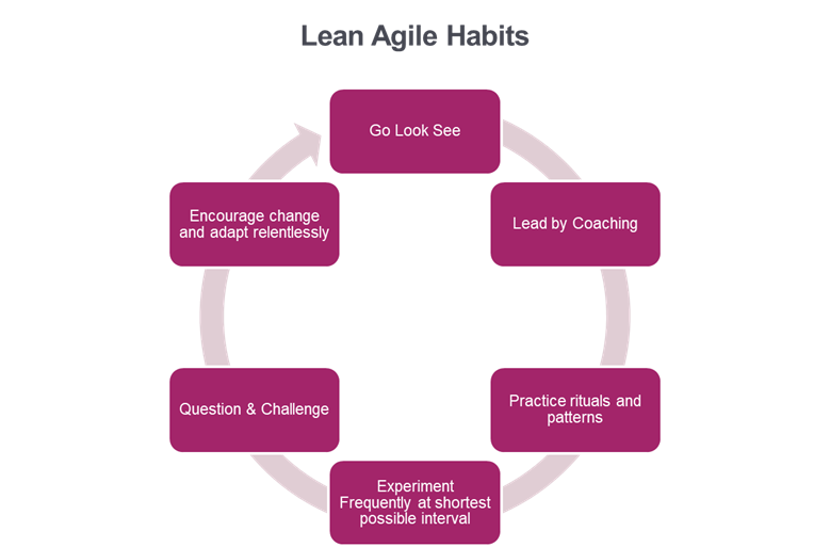

Behaviors as an observable action

Challenging and changing behaviours were an important part of creating the right conditions in which to success. So we spent time developing a common set of positive behaviours and productive habits that we would all want to live and breathe.

We were then able to support each other in practicing and improving our behavioural skillsets, and through coaching and process confirmation we were all able to benefit from a culture of constructive criticism. Of course at times this was very uncomfortable, but as levels of trust grew amongst the teams These sort of conversations were normalised, and proved extremely beneficial, with some team members commenting that they felt empowered by the feedback.

Leadership Shadow

One of the most difficult things we did was to completely change the work culture. We went out of our way to destroy all of the perceived hierarchies and did everything we could to ensure that all team members felt that they actually owned the project themselves. Everyone is valuable, because everyone contributes in some fashion.

When a team upscales, it is often impossible to spot and fix every issue, or to understand every risk, or to instantly know the answer to a problem. When things did go wrong we tended to try and resolve them through dialogue, which meant more meetings, and more what was perceived as oversight. Our intentions were good, but we came to realise that time is the most precious commodity, and be perhaps burned up a good deal of work capacity.

We came to realise that if we reduced oversight and shifted towards allowing the teams to work through and find an elegant way to address their issues, how much more powerful that management style could be. We concluded that the management role was to empower – to set the vision, enable alignment, coach, don’t fix, have may more trust in employees to take responsibility, and allow their potential to flourish naturally.

Continue Exploring the Unexplored

There is plenty of literature offering specific frameworks, ideas and approaches to project management – and we’re sure that, if different circumstances different techniques will work better than others. In many ways, we think the most important lesson is to just get started.

Think about what you are doing today – you could probably identify some disconnects in how your operation works, so why not conduct some experiments to see what could work better for you. And never forget that anyone in the team could have the one precious insight or suggestion that would make everybody’s life just a little bit easier, more productive and ultimately satisfying

Whilst there were some very testing times we had the privilege of working with some great people on our fabulous ‘Exploring the Unexplored’ learning experience – and we have summarised some of the key principles and insights that may be of significant value to you.

Key Reflections

- Above all else, it’s about how you think: understand how your thinking influences your behavior, and recognise that being open is not a weakness, it’s a superpower!

- Strive for a shared understanding of the goals, key principles, and expected behaviours: if you are all pointing in the right direction you can improve alignment, engagement and productivity across the team

- The shadow of the leader is incredibly important: it is a choice to show up and contribute. Always think about how your actions may directly influence the behaviour and attitudes of others

- Strike a balance between focusing on structure and behaviours: a different focus will required at different points in the journey – you need to be flexible and reactive

- Do not assume you can start at the end of someone else’s journey: a crucial element of the journey was collaboration – creating an open, learning environment empowers a team, allowing it to become self-sustaining

- One size certainly does NOT fit all: beware slavishly following a paint-by-numbers approach. Appreciate context and focus on doing what is right, right now.

We hope that our insights may provide some inspiration for you as you embark on your own adventure. We would love to hear about your experience – because we love learning!

Interested in finding out more?

Take a look at the Project 4 Learning Labs storefront on Yocova